Biomimetic clothing and smart clothes

by Chris Woodford. Last updated: December 12, 2019.

Nature is nothing if not surprising. You could spend your whole life learning the wonders of wildflowers, migratory birds, or creatures of the seashore and still discover only a fraction of the things the living world has to offer. Though nature is fascinating in its own right, it can also teach us many ways of improving our own lives; indeed, it's been a constant source of inspiration for inventors. Some fashion designers and clothing manufacturers are now turning to nature for help in developing biomimetic clothing, which performs more effectively by mimicking the wonders of the biological world. Others are getting as far away from nature as possible with smart clothes, based on cutting-edge electronics and computing. Let's take a closer look at these two, radically different ways of creating hi-tech clothes!

Photo: Now that's what I call a fur coat. Can animals like these musk oxen inspire us to design warmer human clothes? That's what biomimetics is all about. Photo of musk oxen on Nunivak Island by courtesy of US Fish & Wildlife Service.

Biomimetic clothing—learning lessons from nature?

When a German engineer called Otto Lilienthal (1848–1896) strapped

wings to his arms and jumped off a hill in an attempt to fly, many

people thought he was crazy. They had a point: he did, eventually, kill

himself trying to fly like the birds. But his pioneering glider

experiments inspired the Wright brothers to develop their

engine-powered

Photo: Reinventing flight: Biomimetics doesn't always work. To begin with, humans tried to fly by flapping wings like birds. People only successfully took to the air when they thought about the problem a different way and stopped copying nature so literally. The Wright brothers making their historic powered flight at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina in December 1903. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Lilienthal the "birdman" is only one example of how nature has

inspired inventors. How about the story of British engineer Marc

Isambard Brunel (1769–1845), father of famous engineer Isambard Kingdom

Brunel (1806–1859), who invented a new way of digging tunnels

underwater after watching a worm burrowing through the

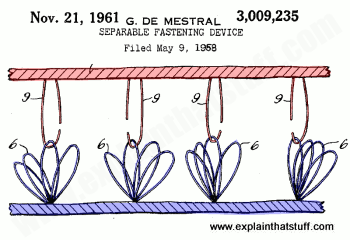

Photo: VELCRO®: George de Mestral's amazingly useful two-part textile fastener was directly inspired by nature. This is a diagram of the hook-and-loop mechanism sketched in his original patent US Patent 3,009,235: Separable fastening device (filed 1958, granted 1961). Artwork courtesy of US Patent and Trademark Office.

Before synthetic textiles such as

How can soggy sheep keep you warm?

If you've ever gone walking on a mountain in winter, you've probably

marveled at how sheep can survive in damp, cold, and utterly horrible

conditions. The explanation is simple: wool is an amazingly good

Photo: Sheep are built to stay warm, even when they're wet.

Several brilliant features make merino the perfect thermal underwear

for sheep. First, it has much finer fibers than ordinary wool.

Finer fibers means more fibers and more air

trapped between them. It's trapped air that gives you warmth in

clothing (that's why wearing several thin layers is generally warmer

than wearing one thick pullover). You can also fluff up the surface of

merino so the fibers occupy more space and trap even more air—giving

more thickness and insulation with no added weight. All dry wool (and

merino wool in particular) has an amazing ability to mop up steamy

moisture from inside it and merino can absorb over a third of its own

dry weight in water. As perspiration soaks into the fiber, it turns

from a gas to a liquid, giving off what's called latent heat of fusion.

The water molecules actually lock onto the wool fibers making chemical (hydrogen) bonds with them.

Bonded molecules are more stable than unbonded ones, so the chemical bonding process

releases energy, giving off what's called heat of sorption that keeps you warm.

That's significantly different from what happens with synthetic fibers.

If you wear polyester clothes and you sweat, the sweat will evaporate

from your skin and cool your body down, which probably isn't too

helpful if you're climbing a mountain in midwinter. But if you're

wearing a merino base layer and you start to sweat, the merino will

lock away the moisture and give off

Will clothes ever clean themselves?

Photo: The leaves of the lotus plant (Nelumbo nucifera) are self-cleaning. Photo taken in the Wichita Mountains National Wildlife Refuge by Elise Smith, courtesy of US Fish & Wildlife Service.

One of the most irritating things about clothes is that you have to

keep washing them to keep them clean. Animals wash, clean, and preen

themselves too—but you don't often see plants doing the same thing.

That's because some plants, like the lotus, have a clever

built-in mechanism that naturally keeps them clean. The leaves are

coated with

Why does it help to swim like a shark?

Skin is an amazing material: it's waterproof, it's breathable, it

helps to regulate our body temperature, and it can repair itself

automatically. One thing it was never designed for was

Photo: Unlike humans, sharks are designed to slip easily through water. Photo of navy divers and sharks at the Newport Aquarium, Kentucky, by Davis Anderson, courtesy of US Navy.

Now you might think super-smooth suits would work better than rough ones as you swim through the pool, but the Speedo company's Fiona Fairhurst noticed something surprising: sharks have quite rough skin and still manage to swim fast. That was one of the key insights that powered the development of a revolutionary new Speedo swimsuit. Known as FASTSKIN®, the tight-fitting suit is covered with tiny v-shaped channels, just like the ridges (technically known as placoid scales or dermal denticles) on a shark's body. The idea is that water whizzes along these channels, reducing the frictional drag (essentially, turbulence) between the water and your skin, so you can swim faster.

Another of Fairhurst's important insights was to realize that a swimsuit could be engineered to force a swimmer's body into a more effective posture. So Speedo's suits fit very tightly, squeezing your body into a shape that reduces form drag (the basic resistance that the shape of an object offers as it pushes through water or air). Compressing muscles helps to reduce fatigue, so the suits also help you swim faster for longer. According to Speedo, swimsuits like this can boost a swimmer's speed by up to 3 percent. It's hardly surprising that many champion swimmers now wear suits like these. At the 2004 Sydney Olympics, swimmers kitted out in FASTSKIN earned an impressive 47 medals.

Why should clothes work like pine cones?

Photo: Pine cones naturally close in wet weather and open up in dry conditions. Something as simple as this could inspire new clothing designs.

You probably know an easy way to tell the weather. Get a pine cone and watch whether the spines open and close. If it's going to rain, the spines close up to protect the seeds inside; if it's going to stay dry, the spines open up to improve the chances of the seeds escaping. Researchers at England's Bath University and the London College of Fashion are trying to design biomimetic clothes that could work the same way. The fabric could be made with an outer layer of tiny spikes, only 1/200th of a millimeter wide. When it's hot, the spikes would open up to let out the heat, cooling you down. When it's cold, the spikes would flatten back down to trap air and provide more effective insulation.

Smart clothes

Biomimetic clothing is ingenious and inspired, but nature doesn't have all the answers. Thankfully, we also have human ingenuity to draw on in the quest for ever more useful clothes.

Clothes for health

What if your sports bra could spot breast cancer or your blouse could sense the strange palpitations of a looming heart attack? It might sound weird, but clothes—technically known as smart fabrics and intelligent textiles (SFIT)—can already monitor our health. Some years ago, a company called Textronics figured out how to build comfortable sports bras and shirts with electrode sensors naturally knitted inside the fabric to monitor an athlete's heart beat. They automatically capture puffs and palpitations and beam the data wirelessly to a monitor you wear on your wrist or stuff in your pocket. Nike+ shoes harness similar technology for health and fitness. A

Photo: Wearable electronics could automatically monitor your health.

Sounds trivial? How about natural-looking, comfortable clothes that elderly people could wear to monitor their movements and anticipate declining health? Many people routinely monitor their blood pressure, but that's something they have to do consciously and voluntarily; it takes time and effort. Smart clothes with built in monitors not only measure standard health indicators like this, but also offer an easy and affordable way to keep tabs on things like changes in gait, caused by progressive conditions like Parkinson's disease or strokes, and to monitor, proactively, whether elderly people are more likely to fall and injure themselves.

Clothes for safety, entertainment, and power

Where health ventures, safety often follows. Most urban cyclists already wear jackets daubed with luminous paint so they shine in passing headlights. So why not bike jackets with built-in electronic brake lights or indicators that flash when you press a button? If you can stitch electrodes into clothes for things like that, why not more frivolous and entertaining things too? Why not skirts with built-in

Flashing and flickering is pretty tame stuff.

And in a world that watches energy use like a hawk, what about turning shirts into solar panels? If you can build conductive fibres into a t-shirt and make it flash with a

Suddenly, the phrase "smart clothes" takes on a whole new meaning!

Books

- Biomimetics for Designers: Applying Nature's Processes & Materials in the Real World by Veronika Kapsali. Thames and Hudson, 2016. A more design-oriented guide.

- Potentials and Trends in Biomimetics by Arnim von Gleich, Christian Pade, Ulrich Petschow, and Eugen Pissarskoi. Springer, 2014. Reviews biomimetic trends in materials science, robotics, medicine, and other areas.

- Engineered Biomimicry by Akhlesh Lakhtakia and Raul Jose Martin-Palma (eds). Newnes, 2013. From VELCRO and artificial muscles to robots inspired by nature and modified surfaces, this book reviews cutting-edge research in biomimetics.

- Biomimetic and Bioinspired Nanomaterials by Challa S. S. R. Kumar (ed). Wiley-VCH, 2010. A collection of scientific papers reviewing a wide range of bio-inspired nanotechnology materials and their everyday applications.

- Biologically Inspired Textiles by Albert G. Abbott and Michael Ellison (eds). CRC Press, 2008. Reviews the basic idea of biomimetics and the production of biomimetic materials, before considering a variety of clothing and other textile applications.

Articles

- Skin Care's Backlash Against Essential Oils by Kari Molvar. The New York Times, September 29, 2017. How biomimetics is inspiring cosmetics designers.

- Injecting Tiny Proteins Into the Hunt for 'Clean Coal' by Gayathri Vaidyanathan, The New York Times, February 16, 2010. Could biomimetics help us solve climate change?

- Biomimetics: Borrowing from Biology by Becky Poole, The Naked Scientists, July 2007. A nice introduction to the whole topic of biomimetics. Includes lots of stuff about gecko adhesives and self-cleaning lotus flowers.

- Biomimetics: The Economist, June 9, 2005. A general review of biomimetics and the technological benefits it might bring.

- Eluding the enemy by Peter Forbes. The Guardian, January 16, 2003. How military clothing uses biomimetic inspiration to improve camouflage.

Patents

- US Patent: 6,446,264: Multi-functional animal garment that reacts to changing temperatures and activities by Jan Antoinette Buehner, 15 May 2008. A textile that opens and closes to allow heat and moisture to escape, much like an opening and closing pine cone.

- US Patent: 6,446,264: Articles of Clothing by Fiona Fairhurst et al, Speedo International Limited, 10 September 2002. One of the Speedo FASTSKIN patents for a swimsuit contoured to match key muscle groups.

- US Patent: 4,972,522: Garment including elastic fabric having a grooved outer surface by Leonard J. Rautenberg, 27 November 1990. An early patent describing how roughened fabrics can improve the performance of a swimmer.