Defibrillators

by Chris Woodford. Last updated: November 1, 2020.

Charging.... five hundred... clear! We've all watched it happen on ER dozens and dozens of times, but it's still relatively uncommon to

see the same thing in real life. When someone collapses with a cardiac

arrest, their heart can go into a kind of quivering limbo called

fibrillation. One of the most effective ways to get it going again is

with a sudden powerful

Photo: Ready for action: You can't save a life with a defibrillator if there isn't one around to use. That's why many more of these units are now popping up in public places. This is a wall-mounted unit on a railroad station in England.

Contents

Why do we need defibrillators?

Photo: Conventional CPR (heart massage and artificial respiration) can be invaluable, but may not be enough to save a patient without defibrillation. Photo by Suzanne M. Day.

You might not think of yourself as having lots of muscles, but

there's one super-powerful muscle in your body you absolutely depend

on: the tireless blood

What is a defibrillator?

As the name suggests, defibrillation stops fibrillation,

the useless trembling that a person's heart muscles can adopt during

a cardiac arrest. Simply speaking, a defibrillator works by using a

moderately high voltage (something like 200–1000 volts) to pass an

The kind of defibrillator you see on In units designed to be used by less-trained people in public places, sticky,

self-adhesive electrode pads are often used instead of paddles for

safety and simplicity: once the pads are stuck on, the operator can

stand well clear of the patient's body and that reduces the risk of

their getting an electric shock.

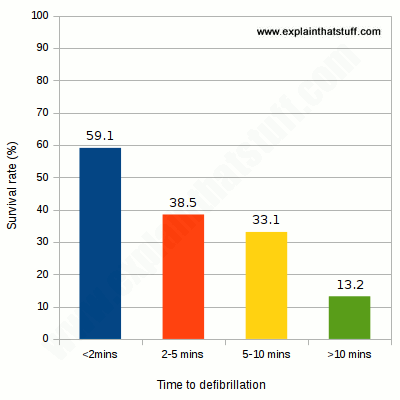

Chart: Why we need more public access defibrillators: the chance of surviving an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest increases the more quickly defibrillation is used. Data from a study of 1732 cases in North Carolina by

C.M. Hansen et al, 2015.

You might have noticed that there are lots more defibrillators in public places than

there used to be—and there have been calls for them to be as commonplace as

fire extinguishers. The reason is simple: if someone collapses with a cardiac arrest,

immediate defibrillation, even by an untrained bystander

following step-by-step instructions, dramatically increases the chance of survival,

compared to delayed defibrillation when the emergency medical services eventually

arrive. A 2014 Australian study found

the survival rate to be 45 percent compared to 31 percent; very favorable outcomes

have also been found in studies in

Osaka, Japan,

Los Angeles, California,

the UK,

and elsewhere. The effectiveness of public defibrillators seems certain to increase now that more areas are encouraging public CPR and AED training

in schools and colleges. Over the last decade, a number of US states (including Arizona, Georgia, Nevada, Rhode Island, and Texas) have passed laws encouraging or requiring secondary pupils to receive training of this kind before they leave school.

Even so, as a thoughtful 2018 review from Scandinavia points out, it's important to remember that many cardiac arrests take place inside people's homes and in other places where debrillators are not widely available, so their use is still limited. “Out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) is a major health problem, accounting for approximately 700,000 annual deaths in the United States and Europe. Early defibrillation is one of the most important determinants of improving survival.” M. Ring et al, 2018 Photo: A portable external defibrillator packed away in an ambulance. Photo by Charles Larkin Sr courtesy of US Air Force. The units you're likely to see in railroad stations and other

public areas are called automated external defibrillators

(AEDs) or public access defibrillators (PADs)

and they're designed to be used with little or no training.

They have self-adhesive electrode pads and a built-in computer that

automatically analyzes the patient's heart rhythm to figure out

whether a shock will help them (defibrillation doesn't work if the

heart has stopped beating altogether) and, if so, what level of shock

is appropriate. The units you see in TV hospitals and ambulances that feature

handheld paddles and gel applied to the skin are usually manual

external defibrillators. With these devices, the doctors, nurses,

or paramedics have to figure out themselves whether defibrillation

will help and also what shock voltage or energy level to use.

Semi-automated defibrillators can work either automatically or

in a manual override mode if the doctor prefers. Patients who suffer regular problems with their heart rhythm

sometimes have an internal defibrillator permanently implanted into their chest

(a bit like a pacemaker) or worn on the surface of their skin under

their clothes. Units like this constantly monitor the heart rhythm

and deliver a shock whenever it's needed.

Photo: Two different ways of applying the charge: 1) Conventional paddles on a manual defibrillator. Photo by Christopher Hubenthal courtesy of US Air Force. 2) Self-adhesive electrodes (with printed graphics showing you where to stick them to the patient's body) on an automated defibrillator. Photo by William Greer courtesy of US Army.

How effective are defibrillators?

Types of defibrillators